A decision to plead guilty is a difficult one, especially when a criminal defendant is facing a life sentence without the possibility of parole. In 1927, the U.S. Supreme Court in Kercheval v. United States said that “a plea of guilty differs in purpose and effect from a mere admission or an extra-judicial confession; it is itself a conviction. More is not required, the court has nothing to do but give judgment and sentence.”

Historically, guilty pleas were viewed as the first step toward individual rehabilitation through the acceptance of responsibility for one’s criminal actions. Judges and prosecutors viewed this acceptance of responsibility as deserving of lenient sentencing. Jury trials, it was assumed, were reserved for searching and finding the truth. A not guilty verdict was widely accepted as evidence of the truth. A guilty verdict by a jury, on the other hand, was viewed as an attempt by a criminal defendant to “beat the system.” Because a jury verdict of guilt was considered infallible, it was automatically accepted as a rejection of a defendant’s attempt to escape responsibility for his actions, demanding a harsher punishment than one given following a guilty plea.

This historical process invited abuse. It led to the corrupt but judicially accepted practice of plea bargaining: a process is which a defendant seeks the shortest sentence possible in exchange for his guilty plea, thus saving the government the time, expense, and even the inconvenience of a trial. The process shifted from acceptance of responsibility to making the best deal possible. Prosecutors quickly realized that a defendant’s receptiveness to bargain for a reduced sentence opened the door for the government to move from a process of inducing a guilty plea to a process of demanding a plea with the threat of a much harsher sentence if the defendant does not acquiesce.

The courts approved this corrupt process that has nothing to do with seeking or finding the truth. The primary goal today in the administration of justice is expediency and resolution—take the deal or accept the worst consequences.

This is the process recently faced by Kevin Marquette Bellinger. This federal inmate is facing charges of murder by a federal prisoner serving a life sentence.

Bellinger has already served 16 years of a life sentence following a conviction of assault with intent to kill while armed and additional firearms offenses.

However, certain things about that sentence differ from the one related to the charges he is now facing. Bellinger is housed in a federal facility pursuant to convictions obtained in the District of Columbia. In other words, he is serving time for DC convictions that offer the prospect of parole at some future point.

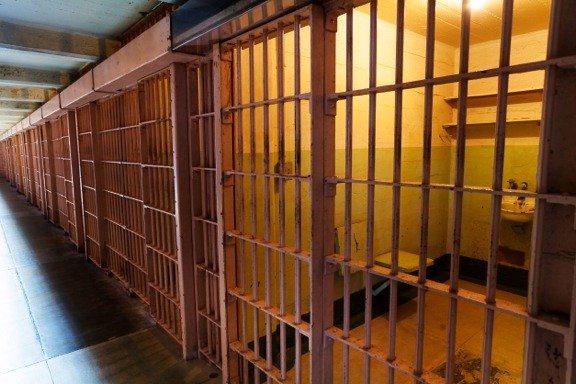

That will not be the case if he is found guilty of the federal homicide charges he currently faces. Instead, he will spend the rest of his life in prison without the possibility of parole with the only hope of release coming from executive clemency action.

Because of this, and because Bellinger maintains that he is innocent of the crime that he has already served 16 years for, he decided to reject a possible plea deal offered by the government in the federal case that could have resulted in a lesser sentence than life without parole.

What Happened to Land Bellinger His Current Charges?

In 2007, federal prisoner Jesse Harris was fatally stabbed 22 times. Bellinger and another prisoner, Patrick Andrews, were accused and charged with Harris’s murder.

Bellinger was convicted for the murder, but the conviction was overturned by the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals last June in an unpublished opinion. The appeals court ruled that the trial court should have allowed Bellinger through a defense witness to give testimony that the victim had reportedly stated he was about to “slam a knife in somebody” shortly before his slaying, opening the door for a Bellinger defense that he killed the victim to protect Andrews.

With the plea deal rejected and the consequences of that decision having been fully explained to him by the district court, Bellinger now faces a jury trial in July.

Federal Homicide Convictions Often Result in a Life Sentence

There are multiple different federal crimes related to murder (including murder, manslaughter, foreign murder by United States nationals, murder by escaped prisoners, and so on), but most of these charges come with the possibility of a life sentence. First degree murder convictions always come with life in prison. Second degree murder convictions give the judge the ability to sentence the defendant to imprisonment “for any term of years or for life.”

Homicide is one of the most severe crimes a person can be charged with. If you have been charged, or are afraid you may be charged with federal homicide, get on the phone with a federal defense lawyer now.